How the Current Catastrophic Situation in Armenia Began: From Romanticized Independence to Systemic Vulnerability – Part 1: LEVON TER-PETROSYAN – THE ARCHITECT OF POST-SOVIET VULNERABILITY (continuation)

Privatization or Collapse? Great Factories Turned to Scrap

“A country without industry can no longer stand on its feet.”

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Armenia inherited not only a flag and an emblem, but also something that seems almost unimaginable today: industrial giants, scientific-research institutes, high-capacity design bureaus — an entire industrial civilization created through decades of intensive work. In the hands of farsighted reformers, it could have become the foundation of a new economy, a launchpad to the future. Yet 1992 and 1993 entered history for very different reasons.

The privatization launched under the government of the Armenian Pan-National Movement (APNM) - according to critics of that period - turned into a hurricane that swept away everything in its path. Redistribution instead of reform, dismantling instead of development, empty enterprise offices instead of modernization. The skeletons of once-effective enterprises still stand on the outskirts of towns like monuments to a future that never came.

The Yerevan Machine-Tool Factory - the pride of industrial Armenia, a legend of engineering prowess -was dismantled and exported piece by piece, according to witnesses, like a gigantic organism disjointed for quick profit.

The “Mars” Scientific and Industrial Enterprise, once producing integrated circuits and electronic equipment, was left paralyzed, cut off from power supplies, and eventually abandoned.

The vehicle aggregates plant, the aluminum plant, instrument-making factories, dozens of production enterprises from Gyumri to Yerevan - everything was disappearing so quickly that even residents of other post-Soviet countries were shocked: “How did you manage to destroy everything so quickly?”

That wave came wrapped in slogans about a “transition to a market system” - slogans that were false, questionable, or, according to economists who tried to halt the destruction at the time, simply premature.

“When a house is destroyed, there will always be someone ready to buy the bricks. But who buys the future?” wrote Shirvanzade in his novel “Chaos”, as though speaking directly to our era.

Decisions were made rapidly, almost in a blink. President Levon Ter-Petrosyan advocated shedding “the Soviet burden.” Later, it became clear that for a small country, this had not been a burden at all, but the last stronghold — the final bastion of economic defense — which should never have been surrendered so hastily. Many recalled Paruyr Sevak’s words at the time:

“If a single tree is cut, a new one can still be planted. But when an entire forest is cut, the desert comes forever.”

These words matched the realities of the 1990s with frightening precision.

Enterprises were disappearing not because they lacked prospects, but because they offered easy money to a small circle of people. Scrap metal was exported, buildings were abandoned, and highly qualified engineers were driven to sell sneakers at the market - this is how the new “economic model” began to take shape.

The words of an elderly metalworker from the Yerevan Machine-Tool Plant echo in my mind. Watching the production halls being cut apart with gas torches, he told journalists:

“We built it in 40 years. They destroyed everything in 40 days. Only card houses - and a state - can be destroyed so quickly.”

Suspension of the Armenian NPP: An Ideological Fire the Entire Country Paid For

Developments around the The developments surrounding the Armenian Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) were another fatal decision of the early 1990s — one that still fuels heated debate. Hardly had Armenia torn itself away from the vast but already crumbling Soviet Union when its new APNM leadership, swept up in the euphoria of revolutionary romanticism, tried to teach the country new rules of nature and political morality. To them, the Armenian NPP - our only shield against cold, blockade, and darkness - became a symbol of the “Soviet era”, something they believed had to be rejected for the sake of joining the “civilized world.”

All of this unfolded amid the still-open wounds of the 1988 earthquake and the political elation of the first months of the independence movement. Environmental activists within the APNM - led by Ashot Manucharyan, Raffi Hovhannisyan, and Andranik Kocharyan - issued harsh statements, calling the nuclear plant a “mine under the country.” Their arguments were emotional, and the rallies were large and fervent.

In 1990–1991, the pressure grew. Armenia was eager to show the West that its new government was “well-informed,” “environmentally responsible,” and committed to modern safety standards. In that context, the reactor, which had been shut down in 1989, was fully conserved.

Thus, in a country where gas was in short supply, and electricity came in long, unpredictable intervals, the fate of the NPP became an ideological sacrifice to the spirit of the new era.

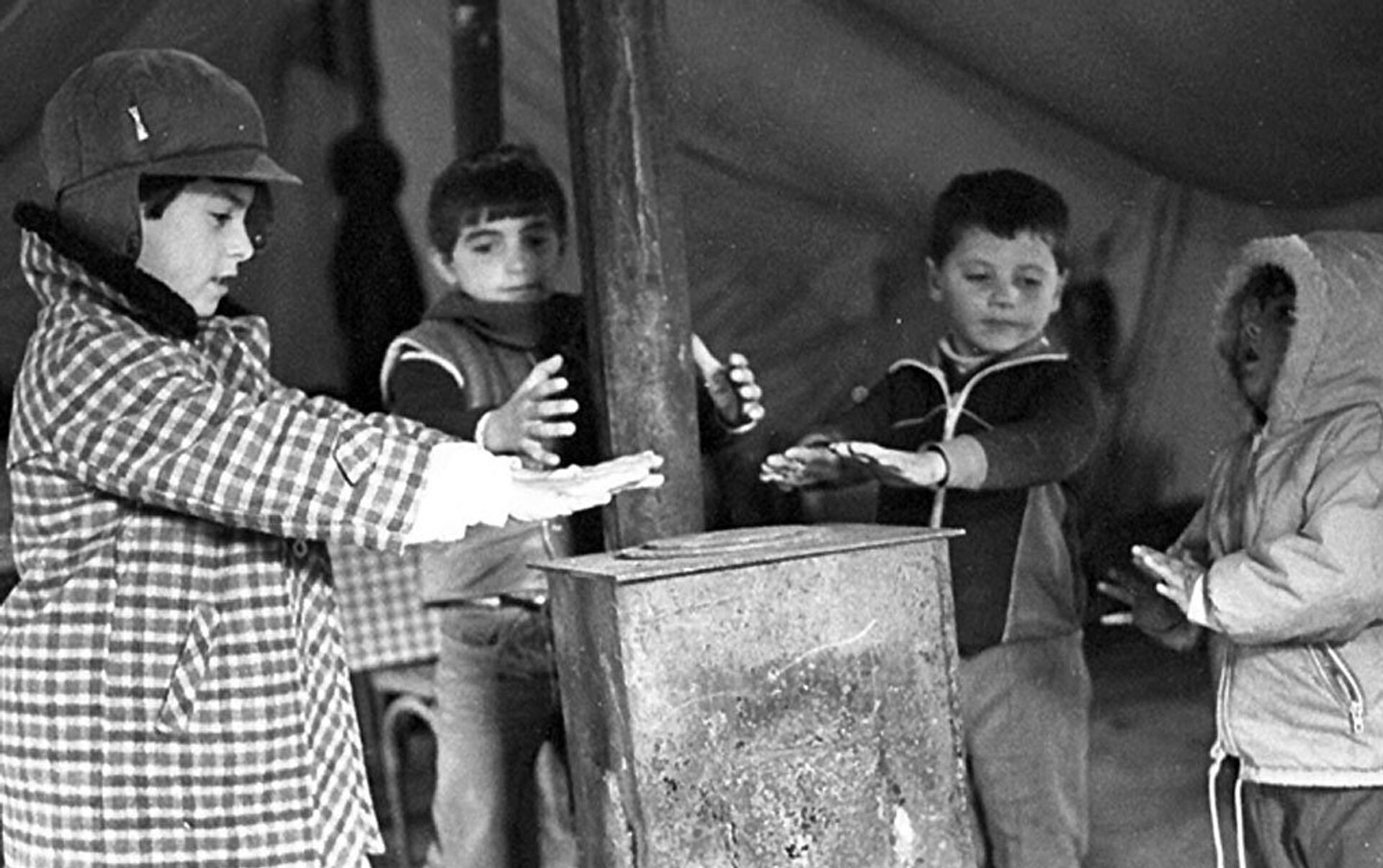

It was the beginning of a long winter. Wind shook the broken windows; people taped newspapers over the frames, trying to keep the cold out. City streets, drowned in darkness, looked like sets from a post-apocalyptic film.

Residents of Yerevan will never forget the kerosene lamps glowing in windows, the trees cut from streets and parks to heat homes. Smoke instead of light; soot-grey traces where warmth should have been.

“Mistakes made in a fit of passion are corrected by time. Mistakes made out of ideology can be corrected only by catastrophe.” (Unverified quotation; translated from Russian.)

It seemed as though Mill had known about us — about the people standing in long queues for kerosene, about hospitals where surgeons operated by the light of a portable lamp, about the enterprises shutting down one after another not for lack of demand, but for lack of electricity.

The suspension of the NPP triggered a chain reaction: metallurgical shops closed, machine tools went silent in factories, production lines stalled at the Yerevan Machine-Tool Plant, the presses stopped at Mars, and factories and industrial giants fell into agony.

Enterprises sank into bankruptcy, as if someone were stripping them to the bone. People went months without salaries, and equipment decayed. Against this backdrop, voucher privatization took shape. When people are left without bread and in darkness, they are forced to sell their vouchers for almost nothing — and that is exactly what happened.

The recollections of a former engineer at the “Mars” Scientific and Industrial Enterprise vividly capture the era (published in “Hayk” Newspaper, Issue No. 12, 1998):

“I still remember how cold it was in our production shop. It was five degrees below zero. We would come to work, put a kettle on a small kerosene stove, and that was the only sound. No machine tools were running. Our bosses bought our vouchers for the price of two loaves of bread.”

Another example, from an interview with a former member of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Armenia (published in “Aravot” Newspaper, Issue No. 34, 2001):

“People were freezing, in darkness — real, tangible darkness — while ideologists talked about ‘European environmental standards.’”

The Press of the Time as a Fragment of the Epoch

- “The suspension of the NPP is a goodwill gesture to the world community,” — “Haykakan Ashkharh”, Issue No. 23, 1990.

- “The country cannot live by the light of kindles,” said energy expert A. Khachatryan — “Golos Armenii”, Issue No. 5, February 1991.

- “If the reactor is not re-launched, the industry will collapse,” — “Komsomolets,” Issue No. 212, November 1992.

These headlines read like a chronicle of slow descent into icy darkness, testimony to a people realizing that ideology had triumphed over common sense. Without quoting the classical Armenian writers, it is impossible to capture the atmosphere of those years.

- “The country plunged into darkness, but darkness penetrated also into the people” — words attributed to Paruyr Sevak by the publicists of the 1990s.

- “A nation waking in the dark hears only the breathing of the frozen soil.” — Silva Kaputikyan, poet (1991).

These words seem written not with ink, but with the cold that seeped into every house at the time.

The suspension of the NPP was not merely a technical decision; it was an ideological choice made in the heat of romantic political euphoria. Its consequences, however, were real, tangible, and painful:

- Drop in living standards,

- Shutdown of the production sector,

- Bankruptsy of enterprises,

- Sale of vouchers,

- Large-scale migration.

Each of these outcomes was the sad logic of the epoch — the country paid too high a price for its ideals.