How the Current Catastrophic Situation in Armenia Began: From Romanticized Independence to Systemic Vulnerability – Part 3. The Era of Robert Kocharyan (1998-2008)

Imitated Transition: How Robert Kocharyan Rose to Power and Why It Was Deemed Necessary

Robert Kocharyan’s rise to power in 1998 was the outcome of a multi-step political combination unfolding between 1996 and 1998. Levon Ter-Petrosyan’s resignation, which at first glance appeared to stem from disagreements over the Karabakh settlement, became a turning point: after victory in the First Karabakh War, society was not prepared to accept capitulation.

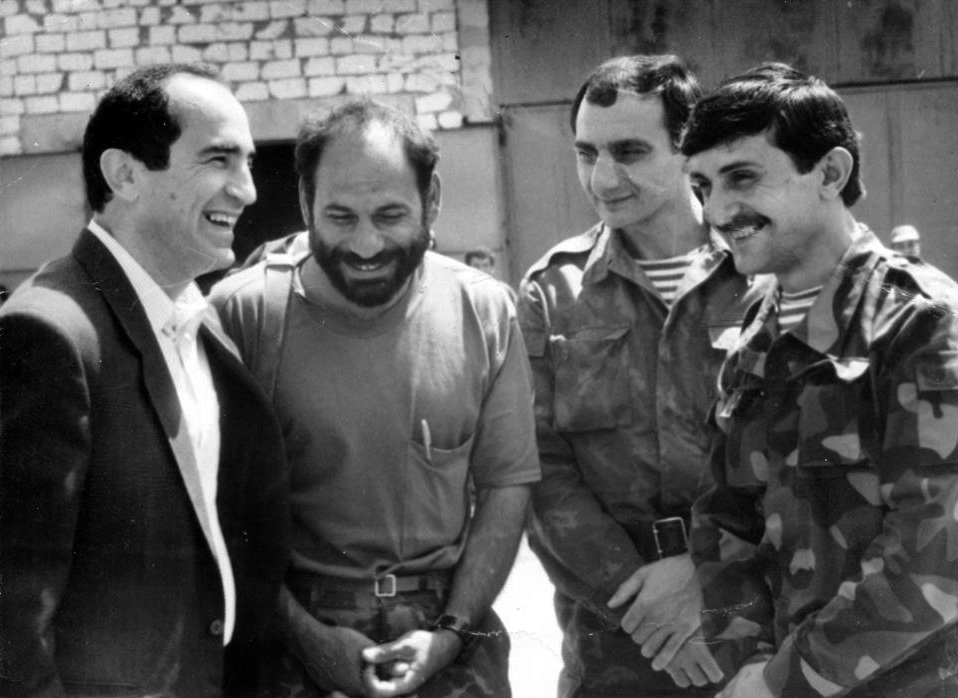

Kocharyan’s Meteoric Career Was Far From Accidental

The defining feature of this period was Robert Kocharyan’s remarkably rapid ascent, marked by a largely non-typical political trajectory. After a relatively brief tenure at the helm of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic - first elected in December 1994 as President of the NKR Supreme Council, and later reaffirmed in his mandate through nationwide presidential elections on November 25, 1996 - Kocharyan was invited to Yerevan and offered one of the highest positions in the Armenian state.

Just months after his reelection in Artsakh, on March 20, 1997, Kocharyan was appointed Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia. The decision was unprecedented and gave the impression of a carefully planned scenario: the leader of an unrecognized state suddenly became the second most powerful figure in an internationally recognized one within an exceptionally short period. Such a development hardly fitted the logic of spontaneous political appointments.

This naturally raises a reasonable question: why organize nationwide elections in Artsakh only to leave the post within a few months and relocate to Yerevan?

Resignation as a Staged Performance: A Version of Ter-Petrosyan’s Orchestrated Exit

Levon Ter-Petrosyan’s resignation did not resemble the outcome of political defeat or irreconcilable disagreements. Rather, it bore the hallmarks of a deliberately staged performance, played out according to a pre-written script. The core objective of this scenario was to initiate the so-called “Goble Plan” — a project involving territorial swaps — the implementation of which was deliberately entrusted to Robert Kocharyan.

Within this framework, Kocharyan did not act as an independent political figure, but rather as a convenient executor of decisions made elsewhere. He was integrated into an existing power consensus and operated under the dominant influence of Vazgen Sargsyan, who controlled the key levers of power. From this perspective, Ter-Petrosyan’s resignation was neither a defeat nor a gesture of political responsibility. It functioned as a technical component of an orchestrated transition: a change of figures without altering the strategic military-political course, designed to prepare society for the most painful concessions.

Subsequent developments only reinforced the sense of a carefully managed transfer of power. Re-elected President of Armenia in 1996, Levon Ter-Petrosyan stepped down on February 3, 1998 - less than two years into his second term. While the official explanation cited disagreements over the Karabakh issue, the timing and coordination of political moves cast serious doubt on the spontaneity of these events.

This opens the door to a broader interpretation. The U.S.-backed plan to resolve the Karabakh conflict through territorial concessions by Armenia encountered strong domestic resistance. Under such circumstances, a different configuration may have been chosen - one that both eased the task of implementation and ensured personal political security for Ter-Petrosyan. The plan could be pursued indirectly, through a political figure enjoying unquestioned authority within the military establishment and among veterans of the First Karabakh War.

From this standpoint, Robert Kocharyan - one of the leaders of Artsakh’s defense, closely associated with victory and armed resistance —emerged as the most suitable candidate to advance such decisions. This model made it possible to soften public opposition to painful concessions, redistribute political responsibility, and temporarily stabilize the power system by relying on the trust of the army and war veterans.

Territorial Swap as a Hidden Agenda: From Ankara and Washington to the Kocharyan–Aliyev Face-to-Face Talks

It is noteworthy that almost immediately after Robert Kocharyan’s election as President of Armenia, negotiations over the settlement of the Karabakh conflict intensified. In early 2025, newly declassified documents from the U.S. Department of State revealed that in the late 1990s Kocharyan and Azerbaijani President Heydar Aliyev held direct, face-to-face talks without mediators. According to these documents, one of the options discussed was a settlement based on a territorial swap, specifically, the transfer of the Meghri corridor to Azerbaijan in exchange for an internationally recognized legal status for Karabakh.

Such an approach implied a radical revision of the post-war regional configuration. Nagorno-Karabakh, where Armenians constituted the overwhelming majority of the population, was to receive an international legal status as part of Armenia, while Azerbaijan would obtain a land corridor through Armenian territory linking it to Nakhijevan. In Armenia, this option was primarily associated with the Meghri region, rendering the negotiations exceptionally sensitive and politically explosive.

Although the proposal is often attributed to Paul Goble, he did not hold a senior official position at the time, and his territorial-swap concept had no formal proposal. Later-declassified documents show that discussions along these lines had begun in the early 1990s at much higher levels and were deliberately kept out of the public domain. Notably, the initiative was not solely Washington’s - it originated in Ankara earlier.

As early as 1992, just one year after Armenia declared independence, Turkish President Turgut Özal informed the U.S. president of this scenario, effectively proposing a territorial exchange as a mechanism for resolving the conflict. The administration of U.S. President George H. W. Bush showed little enthusiasm for the idea, yet it was not removed from the diplomatic agenda.

Under President Bill Clinton, Turkish diplomacy returned to the concept. Declassified U.S. State Department materials indicate that in 1997, Turkish Deputy Foreign Minister Onur Öymen, in a direct conversation with U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott, once again raised the need to “change the boundaries” as a means of settling the Karabakh conflict.

During that exchange, the Turkish side articulated the logic of the deal explicitly: Azerbaijan would renounce its claims to Nagorno-Karabakh, while Armenia, in return, would make territorial concessions to ensure Azerbaijan’s strategic connectivity. Ankara also noted that it had previously discussed this option with Baku and Moscow, and sought Washington’s position on the matter.

The U.S. response was markedly cautious. Strobe Talbott warned that revising borders could push the process beyond the Minsk Group framework and create more problems than solutions, likening the proposal to opening a “Pandora’s box.” At the same time, he added an important caveat: should Armenia and Azerbaijan reach such an agreement solely through negotiations and without the use of force, the United States and the Minsk Group co-chairs would not object.

All of this underscores the covert nature of the talks in the late 1990s, the direct format of contacts between Robert Kocharyan and Heydar Aliyev, and the extreme sensitivity of the issue within Armenia’s political elite. What was at stake was not merely territorial concessions but a scenario that touched upon the very foundations of statehood and the regional balance of power.

Meghri, the State Department, and Radio Liberty: How Kocharyan’s Image as an “Initiator of Concessions” Was Shaped

The unclassified diplomatic documents also reveal a less obvious, yet no less telling, subtext. Beyond outlining the negotiation process, they suggest a discernible attempt to shape a particular interpretation of events —shifting responsibility by portraying Levon Ter-Petrosyan as a politician allegedly distancing himself from the idea of territorial concessions, while simultaneously presenting Robert Kocharyan as the principal initiator of discussions surrounding the Meghri corridor.

In this context, it is important to examine how the unclassified documents of the U.S. Department of State were made public. Their publication by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty was accompanied by a clear emphasis on Robert Kocharyan as the key initiator of the territorial exchange idea —Meghri in exchange for the Lachin corridor. At the same time, the broader context of the proposal’s origins and its years-long promotion by foreign actors was largely ignored. Taken together, this creates the impression of a carefully constructed narrative rather than a neutral release of archival materials. Considering that RFE/RL is directly funded by the U.S. Department of State and that its editorial policy is shaped within the framework of U.S. strategic priorities, both the fact of declassification and the manner in which it was carried out give the impression of a coordinated information and political operation. The objective of such an operation appears quite clear: on the eve of the 2026 parliamentary elections, to form a public image of Robert Kocharyan as the architect of painful concessions and to cultivate a negative perception of his political legacy.

Following the change of power and Robert Kocharyan’s election as President of Armenia, the situation indeed changed. According to the same declassified documents, the idea of a territorial swap was placed on the negotiation agenda under conditions of direct contact between Robert Kocharyan and Heydar Aliyev. Prior to that, all formats proposed by international mediators — step-by-step settlement, package settlement, and the “common state” model — had been consistently rejected by one side or the other. As multilateral negotiations reached a deadlock, the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan shifted to a face-to-face format, attempting to break the strategic stalemate on their own.

According to a series of U.S. Department of State documents later published in the media, the outcomes of these direct contacts marked a turning point. U.S. diplomats and their high-ranking interlocutors noted that in September 1999, Robert Kocharyan agreed in principle to Heydar Aliyev’s proposal of a territorial swap. According to their accounts, the key understanding was reached during a meeting in the Sadarak section of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border.

That meeting was already the fifth between Kocharyan and Aliyev in 1999 and one of the few after which both leaders publicly spoke about their readiness for mutual concessions. The rhetoric on both sides was notably conciliatory: instead of articulating rigid positions, the presidents spoke about the limits of possible compromise and the reciprocal steps each side was prepared to take.

“Robert Sedrakovich (Kocharyan) and I are thinking about what kind of mutual concessions can be made,” Radio Liberty quoted Heydar Aliyev.

“Yes, I must say that we have discussed compromises and how far we can go in the negotiation process,” Kocharyan responded, according to Radio Liberty.

The overall mood at the conclusion of the negotiations was also revealing. Contemporaries noted the demonstrative optimism of the two leaders, who even half-jokingly spoke about future celebrations on the occasion of signing a final agreement. At the same time, no specific parameters of the agreement were made public.

Further details emerged from a diplomatic cable sent to Washington after the meeting by the U.S. ambassadors to Armenia and Azerbaijan. The cable stated that “the prospects for peace are much better than at any time since the conflict began in 1988 because of the efforts of Presidents Kocharian and Aliyev.” It further noted that “in April 1999, President Aliyev, on the margins of the Washington NATO Summit, proposed a land swap. President Kocharian agreed in principle, and the presidents entered an extensive series of discussions.”

Washington’s response was swift. Following the Sadarak meeting, U.S. Vice President Al Gore sent a message to the two sides welcoming the significant progress achieved through direct dialogue, while acknowledging that difficult and painful concessions were under discussion. Nevertheless, the willingness of both leaders to seize the opportunity was described as a politically courageous and far-sighted step.

“I understand that these negotiations involve difficult compromises for both sides, but I also believe that your decision to seize this unique opportunity is wise and courageous,” the U.S. Vice President said.

Another indication of the seriousness of the process was the White House’s decision to dispatch Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott to the region in 1999. His itinerary — Baku, Yerevan, Ankara — reflected efforts to synchronize the positions of key regional actors. In Ankara, during his meeting with Turkish President Süleyman Demirel, Talbott noted that expectations in Baku were so high that, according to the Azerbaijani side, the signing of an agreement could take place within weeks — in November 1999, at the OSCE Summit in Istanbul. In this context, the possibility of reserving time in the schedules of the U.S. president and the secretary of state to attend the signing ceremony was even discussed.

JUST FOR THE RECORD

The Lack of Resistance as Key to Understanding the Domestic Political “Crisis” of 1998

Another noteworthy aspect that emerges from the unclassified documents and public evidence from the late 1990s is the lack of active, fundamental resistance from Armenia’s military and political elite regarding talks on the exchange of Meghri for the Lachin corridor. Neither the position taken by Vazgen Sargsyan nor the general behavior of the security cabinet offers any indication of rigid institutional opposition to the idea of a territorial swap. Serzh Sargsyan’s role is also significant here. He headed the united structure of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Ministry of National Security until June 1999, and after their separation, he continued as the head of the Ministry of National Security until November 13, 1999. Given the sensitivity of the period, it would have been hard to imagine that these negotiations were taking place against the will or despite active resistance from the leaders of the country’s security apparatus.

This silence and lack of resistance contradict the image of "uncompromising opponents" to the territorial swap, a characterization that Levon Ter-Petrosyan himself used when resigning from office. The contrast between this image and the actual behavior of key figures indirectly supports an alternative interpretation: the central actors were not fundamental opponents of the so-called "Goble Plan," and the dramatic political split of 1998 might have been part of a carefully orchestrated political maneuver. In this framework, Ter-Petrosyan’s resignation and Robert Kocharyan’s rise to power can be seen not as the result of an elite conflict but rather as an orchestrated transition designed to pave the way for implementing a more painful scenario — the transfer of Meghri and surrounding territories in Artsakh to Azerbaijan.

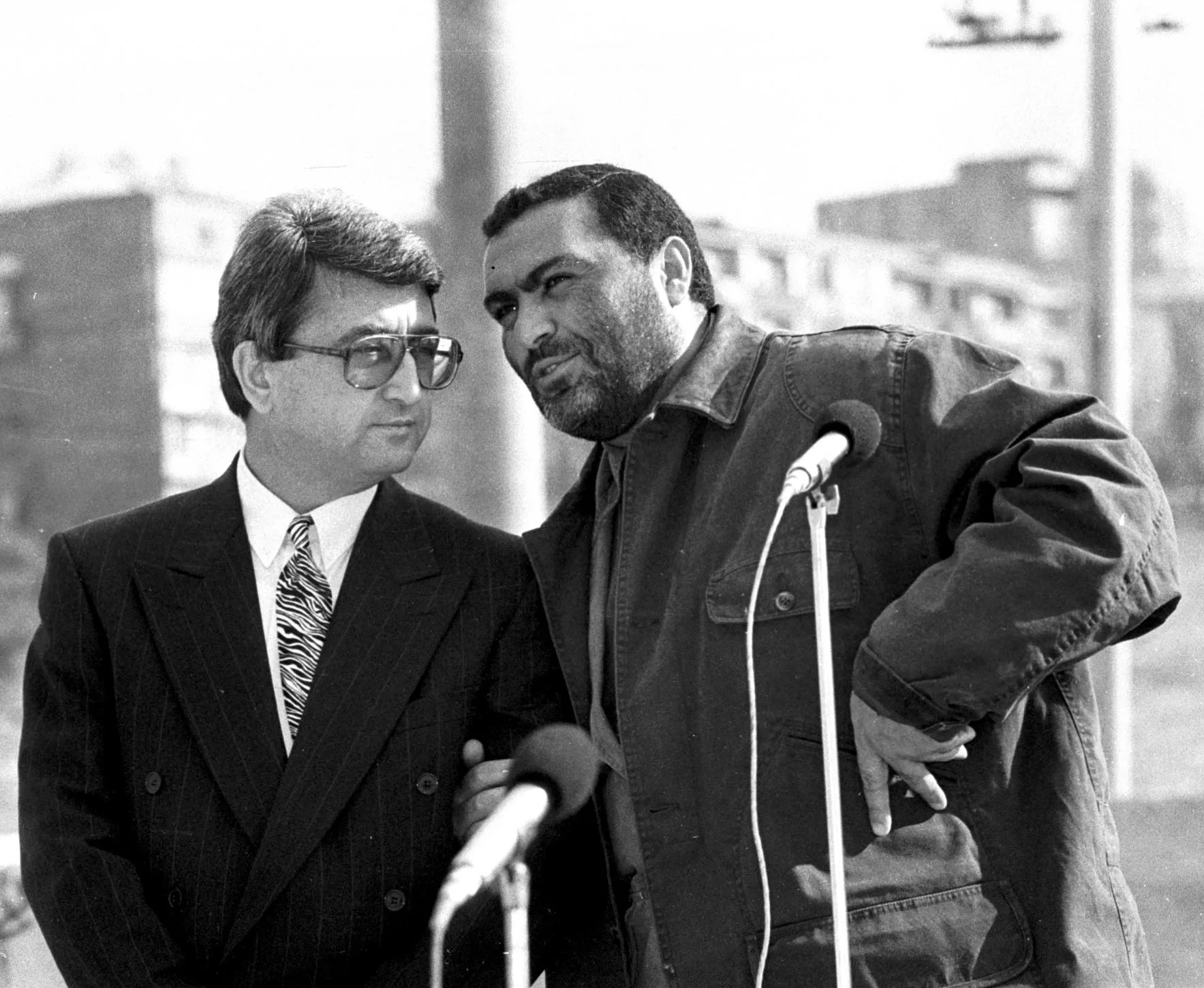

Gunshots in Parliament and Negotiations: A Turning Point in Armenia's History

Returning to the diplomatic efforts of the United States, by the autumn of 1999, the mechanisms set in motion around the Karabakh settlement were operating with an intensity rarely seen in this conflict. Strobe Talbott found himself in a continuous cycle of consultations — Baku, Yerevan, Ankara, and back to Baku. In his assessment, Talbott expressed cautious optimism: a “window of opportunity” had opened, both sides were willing to make painful but historic decisions, and the OSCE Summit in Istanbul could potentially mark the moment when the agreement was signed. The negotiations appeared to have moved beyond rhetoric and were approaching the critical point where diplomacy would culminate in signed agreements.

At that very moment, however, the logic of the negotiations collided with the harsh and unpredictable reality of domestic politics. Just as Talbott was leaving the region — on his way from Yerevan to Ankara — Prime Minister Vazgen Sargsyan, Parliamentary Speaker Karen Demirchyan, and several other key figures were assassinated in the Armenian parliament. Within a few hours, the political landscape of Armenia was irreversibly altered.

These gunshots were not just an internal act of terrorism. They dealt a significant blow to the negotiation process, disrupting the fragile balance upon which the agreements had been based.

In the aftermath of October 27, not only did the power distribution in Yerevan change, but so too did the feasibility of implementing the agreements that had been on the table, including the concessions regarding Meghri. The political space around Robert Kocharyan suddenly shrank: the powerful influence of Vazgen Sargsyan — once a dominant figure in Armenia’s power structure —was gone, and with it, the system of unspoken restrictions that had previously constrained the president’s actions. The tragedy removed the factor of enforcement from the equation, granting Kocharyan a new degree of freedom. This freedom opened up the possibility to revise, freeze, or rethink the arrangements that had once seemed inevitable.