How the Current Catastrophic Situation in Armenia Began: From Romanticized Independence to Systemic Vulnerability – Part 2

GOBLE PLAN: A GEOPOLITICAL TRAP SET IN 1997

Armenia’s late-20th-century history bears little resemblance to a smooth transition of power. Rather, it evokes red-hot metal hastily beaten into shape—under pressure, with miscalculations, amid the collision of global interests. Therefore, when speaking of those who came to replace Ter-Petrosyan, one must first pause and look back, to see how that era was reshaped, instead of merely turning the page.

Ter-Petrosyan’s resignation was neither a defeat nor a triumph of democracy, nor even a “natural end of a mandate.” It was an explosion —delayed, accumulated, and carefully primed - unfolding amid pressure from Washington, Moscow’s cautious resistance, the tense vigilance of Nagorno-Karabakh, and an Armenian elite split between those who feared war and those who understood the price of capitulation.

His resignation was not simply the end of a political biography; it was a boundary. Once crossed, the country was no longer the same. And it did not become what it was supposed to become, either.

Institutionalization of Capitulation: The Ideological Swing of 1997

The summer of 1997 became not only a moment of external pressure, but also a moment of internal ideological rupture, for which Levon Ter-Petrosyan bore personal responsibility. His article “War or Peace: The Moment of Seriousness” was presented as an act of sober realism. In reality, however, it amounted to an ideological formulation of a defeatist logic that was inherently unfavorable to Armenia. Instead of challenging the externally imposed “chess game,” the president effectively accepted the role of a lesser piece, justifying strategic concessions by fatigue from war, rather than by the necessity to continue the struggle.

Paul Goble’s proposal to transfer Meghri merely exposed the fragility of this position. It was not a concession, but a geopolitical amputation: the loss of access to Iran, the undermining of the only real counterbalance to the regional blockade, and the transformation of the country into a dependent transit appendage. Yet Ter-Petrosyan regarded such scenarios as an acceptable price for “peace,” rather than as a red line. His notorious formula - “Karabakh cannot be independent… a compromise is inevitable” - sounded not as a warning to society, but as a predetermined verdict, substituting security interests with the logic of adaptation.

The core problem was not the complexity of the international environment, but the president’s refusal to engage in a political struggle for an alternative. Under the banner of realism, society was offered reconciliation; under the pretext of responsibility, it was urged to lower its sights when national values were at stake. The opposition’s criticism, labeling this approach a capitulation, was not emotional rhetoric. For the first time, Ter-Petrosyan institutionalized the notion that Armenia should consent to strategic weakening in exchange for uncertain external guarantees. In this context, the so-called “moment of seriousness” did not lead the country toward maturity, but rather established a tradition in which concessions are justified as rationality, while resistance is dismissed as irresponsible romanticism.

REACTION FROM NKR: A REJECTION THAT BECAME FATEFUL

Every era has its point of no return. For Artsakh, it came in the summer of 1997, when it became clear that the problem was not only external pressure, but also the domestic political choice made by Armenia’s leadership. While in Yerevan, under Levon Ter-Petrosyan, discussions revolved around a “compromise for the future” and attempts were made to fit Armenia into a diplomatic architecture imposed from outside, in Stepanakert, a systemic threat was already being felt.

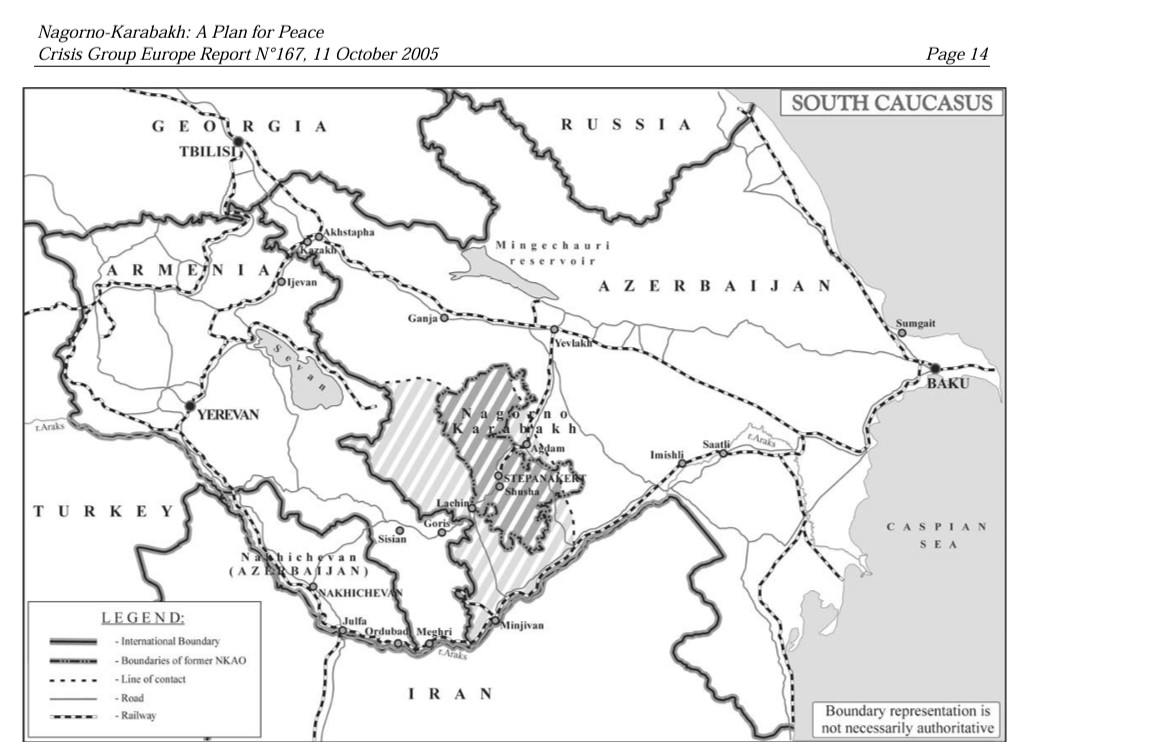

The proposal that entered history as the “Goble Plan” was not perceived in Artsakh as a negotiating position. It was seen as an ultimatum. The transfer of Meghri to Azerbaijan, a narrowed Lachin corridor, and an autonomous Karabakh within Azerbaijan together amounted to nothing less than the nullification of the strategic results of the war. In Stepanakert, it was well understood that peace was not the goal; the goal was the reshaping of the region. And in that new regional configuration, Armenia would no longer be a subject. The idea of territorial exchanges, including proposals involving a corridor swap between Meghri and Lachin, has appeared in international analyses of the conflict’s diplomatic options, such as those explored byThomas de Waal in “Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War.”).

By 1997, Robert Kocharyan was no longer president of the NKR: since March of that year, he had served as prime minister of Armenia. Yet his political and moral legitimacy in Artsakh remained exceptionally high. He was perceived as a representative of the Karabakh line of security, not of the Yerevan school of diplomatic concessions. Kocharyan openly challenged the idea of territorial exchange. Memoirs and recollections from that period frequently cite the categorical rejection of trading land for uncertain peace guarantees: “Land for which blood has been shed cannot be the subject of political deals” (A. Harutyunyan, Memories Without Silence, 2004 (arm.Հիշողություններ առանց լռության, 2004).

This position was fully shared by key military commanders of Artsakh—Seyran Ohanyan, Samvel Babayan, and other senior officers who ensured the region’s real defense. Their arguments were not built on rhetoric or ideology. They rested on geography and military logic: the transfer of Meghri would turn Karabakh into an isolated enclave, and its final occupation would become a matter of time rather than force.

It is noteworthy that the plan also drew criticism at the international level. Analysts warned that a territorial swap associated, among others, with Paul Goble’s name could cost Armenia its vital access to Iran, thereby making the country far more vulnerable from a geopolitical standpoint(for similar assessments, see Salih Yılmaz, review “Land Swap Formula”).).

A number of reports and analytical articles also noted that the idea of a “corridor via Meghri” was viewed as part of a radical redesign of the region’s logistical architecture — a scenario that would entail a strategic deterioration for Armenia without a single shot being fired, while creating a direct Baku–Nakhijevan–Turkey link(for similar views, see International Crisis Group, “Nagorno-Karabakh: A Plan for Peace”).).

Here emerges the key political responsibility of Levon Ter-Petrosyan. His rhetoric about the “moment of seriousness,” and the theses articulated in late 1997, became an ideological justification for concessions that were effectively welcomed in advance, rather than a call for the careful management of risks. Ter-Petrosyan’s formula - Karabakh cannot be independent. Armenia cannot fight endlessly. A compromise is inevitable” - was perceived by many as a verdict of capitulation, issued before any serious attempt had been made to mobilize alternative instruments for protecting national interests.

The critics of the plan were not limited to the so-called “Karabakh radicals.” These concerns were shared by much broader circles: the military, expert communities, and international analytical reports. All pointed to the same risk that the loss of Meghri would become a point of no return for Armenia, fundamentally undermining its strategic position(see, for example, analyses on the “corridors of opportunity” and the consequences of losing Meghri published on ReliefWeb).).

For Artsakh, Meghri was not merely a territory, but an artery of survival. It was Armenia’s only access to Iran, the only direction not controlled by Turkey or Azerbaijan. The loss of Meghri would mean:

- a deterioration of the strategic position without war;

- the transformation of Armenia into a geopolitical dead end;

- the establishment of a direct Baku–Nakhijevan–Turkey link.

What diplomatic documents described as a “territorial swap” was perceived in Artsakh as an inevitable capitulation.

Stepanakert’s rejection of the plan was not dictated by obstinacy or romanticism, but by an understanding of the strategic horizon. This was where the fatal split emerged:

- Artsakh lived in the reality of war and security,

- Yerevan, under Ter-Petrosyan, lived in the reality of diplomatic illusions.

Artsakh was not prepared to place itself on the negotiating table as a bargaining chip, while Yerevan attempted to play a card it did not, in fact, possess. That split was not resolved - it was merely postponed, only to return years later in tragic form, under conditions of a far more unfavorable balance.